Compare your DNA to 168 Ancient Civilizations

FIND THE HISTORY OF YOU

So, you've got your DNA results? To discover who you really are, you need to know where you come from. We can take your DNA results one step further through the use of advanced archaeogenetics

How It Works

Uncovering your ancient ancestry is simple with our three-step process.

Take a DNA Test

Get tested with one of the major DNA testing companies (e.g. AncestryDNA, MyHeritage, FamilyTreeDNA, DanteLabs etc.).

Download Your Raw Data

Download your raw DNA data file from your testing provider's website. We support all major formats.

Upload & Explore

Upload your DNA file to our secure platform and receive your detailed ancestry analysis within minutes.

DIG DEEP

Into Your Ancient History

Your DNA, fully visualized

Explore your roots with exclusive dynamic graphs, interactive maps, and ancestral timelines designed to bring your ancient past to life.

Why Choose MyTrueAncestry

Discover what sets our ancient DNA analysis apart from traditional ancestry services.

100% Anonymous Insights

All retained data is fully anonymized, ensuring your privacy is completely protected.

Powered by Real Ancient DNA

The only service powered by real ancient DNA samples from all over the world and advanced archaeogenetics technologies.

Try For Free

Our basic analysis is 100% free for you to try with no payment method required.

BROWSE OUR DNA SPOTLIGHTS

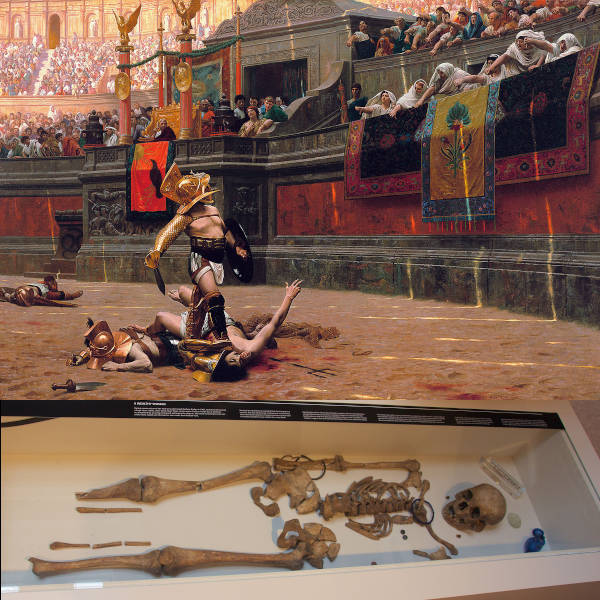

Roman Gladiators from York

The Roman conquest of Britain began in 43 AD but resistance in the north

was fierce. Roman General Quintus Petillius Cerialis led the 9th Legion into the

north and founded Eboracum in 71 AD (which became York) Originally Eboracum was

intended to be a military fortress aligned along the river Ouse measuring about

50 acres in size. This wooden camp was upgraded to stone in 108 AD and

garrisoned by the 6th Legion. The famous Emperor Hadrian reportedly visited

Eboracum in 122 AD in order to plan his great walled frontier, which would be

named after him. Emperor Septimus Severus visited in 208 AD and made it his

private base while campaigning against Scotland, and he became the first of

three Roman Emperors who would die in Eboracum. In 237, the town became a

colonia, the highest legal status any Roman city could attain as Eboracum was

the largest town in the north and the capital of Britannia Inferior. This is

exactly the time period from when these 7 gladiators hailed.

Detailed analysis of these gladiators from York revealed some fascinating

results. The bones showed various degrees of wear and tear as one might expect

from the dangerous sport: 6DRIF-18 revealed a spinal fracture of the first

vertibrae, 6DRIF-21, 6DRIF-3, and 3DRIF-16 meanwhile have fractured forearms,

ankles and wrists. 6DRIF-22 has a skull injury as well as a stab to the neck -

his extra vertebrae did not seem to assist with his fate. 6DRIF-23 meanwhile had

4 cuts to his jaw and was fully decapitated - clearly not the best fate to have.

Last but not least 3DRIF-26 is fascinating indeed - he had a left shoulder

injury, fractured ribs, damage wrists - and from a genetic standpoint is a

deviation from the rest. His background compared to ancient samples from the

time period matches very close to Ptolemaic Egyptians or the Near East.

Read more here

St. Brice's Day Massacre

Aethelred II, known later as the Unready, was King of the English from

978 to 1013 and again from 1014 until his death. He came to the throne at the

age of 12 after his half brother was murdered. At the start of his reign, Danish

raids on English territory began in earnest. Aethelred defended his country by a

diplomatic alliance with the duke of Normandy. The Battle of Maldon on 11.

August 991 AD involved 2,000-4,000 fighting Viking men led by Olaf Tryggvason

against the Anglo-Saxon leader Byrhtnoth who was the Ealdorman of Essex. This

ended in defeat for the Anglo-Saxons and King Aethelred was forced to pay

tribute, also known as Danegeld, to the Danish king. This payment of 10,000

Roman pounds of silver was the first example of Danegeld in England - a pattern

which would follow. The Danish army continued ravaging the English coast until a

Danegeld of 22,000 pounds of gold and silver was paid - at which point Olaf

Tryggvason promised to never return. Viking attacks only grew worse - Danish

raids would follow leading to an even larger Danegeld payment of 24,000 pounds

for peace in the Spring of 1002 AD.

The same year, Aethelred married Lady Emma, the sister of Duke Richard II

of Normandy in hopes of a stronger diplomatic alliance. On St. Brice's Day, 13.

November 1002, the confident yet paranoid King ordered the killing of all Danes

living on border towns such as Oxford. Aethelred described this massacre in his

own words: ... a decree was sent out by me with the counsel of my leading men

and magnates, to the effect that all the Danes who had sprung up in this island,

sprouting like cockle amongst the wheat, were to be destroyed by a more just

extermination, and thus this decree was to be put into effect even as far as

death, those Danes who dwelt in the afore-mentioned town, striving to escape

death, entered this sanctuary of Christ, having broken by force the doors and

bolts, and resolved to make refuge and defence for themselves therein against

the people of the town and the subrubs; but when all the people in pursuit

strove, forced by necessitym to drive them out, and could not, they set fire to

the planks and burnt, as it seems, this church with its ornaments and its

books.

Read more here

French King Louis XVI Mystery

French revolutionists condemned King Louis XVI to death on 21. January 1793

by means of the guillotine at the Place de la Revolution in Paris (roughly where

the Obelisk decorating the Place de la Concorde stands today). After a short but

defiant speech he lost his head as the crowd rushed to the scaffold to dip

hankerchiefs into his blood as momentos. An ornate gourd decorated with French

Revolution themes was recently uncovered which had contained a blood soaked

hankerchief dating to this time. The gourd was allegedly a gift to Napoleon

Bonaparte who became First Consul of France in 1799 and Emperor in 1804. An

anonymous Italian family was in its posession since possibly the late 1800s and

came forward with the relic. It bears an inscription that Maximilien Bourdaloue

on 21. January dipped his hankerchief in the blood of the king. Dried blood was

scraped out and this is the same DNA we present in this DNA spotlight! The

sample contains unsually high and rare markers for the Y-DNA haplogroup G2a.

Louis XVI's direct male line ancestor Henri IV was famous for enacting the

Edict of Nantes which guaranteed religious liberties to Protestants ending 30

years of fighting between French Protestants and Catholics - he was assassinated

in 1610 by a French Catholic zealot. The remains had been presumed lost in the

chaos of the French Revolution after a mob of revolutionaries desecrated the

graves of French kings in the royal chapel of Saint-Denis in Paris in 1793.

However, the head was passed down over the centuries by secretive private

collectors and positively identifed in 2010 with a radiocarbon date between 1450

and 1650. The features were consistent with the king's face including a dark

mushroom-like lesion near the right nostrial, a healed facial stab wound and a

pierced right earlobe. The hair color and moustache and beard on the mummified

head fit the appearance of the king at the time of his death as well as matched

his portraits. Furthermore cutting wounds were visible corresponding to the

separation of the head from the body in 1793 and digital facial reconstruction

of the skull matched the plaster mould of his face made just after his death in

1610. The DNA was then tested and compared to the blood from the gourd.

Read more here

Join Our Community

Our Community blog is your hub for the latest discoveries in ancient DNA, archaeology, and lost civilizations.

Stay curious, stay connected.

Stay curious, stay connected.

Contact Us:

EMAIL

INFO@MYTRUEANCESTRY.COM

MAILING ADDRESS

MyTrueAncestry AG

Seestrasse 112

8806 Bäch

Switzerland