Compare your DNA to 168 Ancient Civilizations

FIND THE HISTORY OF YOU

So, you've got your DNA results? To discover who you really are, you need to know where you come from. We can take your DNA results one step further through the use of advanced archaeogenetics

How It Works

Uncovering your ancient ancestry is simple with our three-step process.

Take a DNA Test

Get tested with one of the major DNA testing companies (e.g. AncestryDNA, MyHeritage, FamilyTreeDNA, DanteLabs etc.).

Download Your Raw Data

Download your raw DNA data file from your testing provider's website. We support all major formats.

Upload & Explore

Upload your DNA file to our secure platform and receive your detailed ancestry analysis within minutes.

DIG DEEP

Into Your Ancient History

Your DNA, fully visualized

Explore your roots with exclusive dynamic graphs, interactive maps, and ancestral timelines designed to bring your ancient past to life.

Why Choose MyTrueAncestry

Discover what sets our ancient DNA analysis apart from traditional ancestry services.

100% Anonymous Insights

All retained data is fully anonymized, ensuring your privacy is completely protected.

Powered by Real Ancient DNA

The only service powered by real ancient DNA samples from all over the world and advanced archaeogenetics technologies.

Try For Free

Our basic analysis is 100% free for you to try with no payment method required.

BROWSE OUR DNA SPOTLIGHTS

Dorset Viking Massacre

On Ridgeway Hill in the County of Dorset, a mass burial was found with the

remains of 54 males. These individuals had all been executed in a gruesome

manner with their decapitated heads dumped together in a large pit.

Interestingly enough all of the sharp blade wounds had been struck from the

front, meaning these individuals had faced their enemy. Radiocarbon dating

showed the bodies were from 890-1030 AD. Strontium isotopes found in the bones

show these individuals were originally from Scandinavia.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which had been written around 890 AD, provides a

year-by-year account of all the major happenings in Anlgo Saxon England.

Aethelred the Unready had been king from 978-1016 AD - it is quite possible

these bodies died during his reign. Initially the king had paid Viking raiders

off with over 10,000 pounds to stop raiding their lands. Later they began hiring

Norse mercenaries to fight off the invading Vikings - however these mercenaries

would switch sides frequently and proved too risky.

Read more here

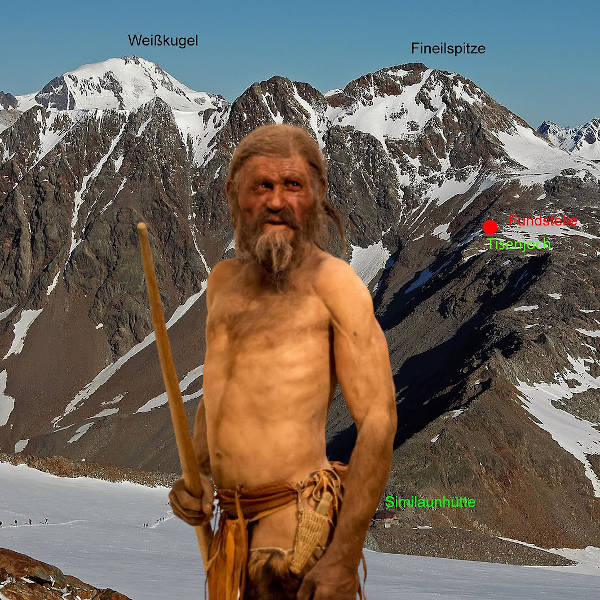

Ötzi the Iceman

In 1991, hikers discovered the mummified remains of a man who died 5300

years ago in the Alps with an arrow stuck through his shoulder. His genetics

show great affinity to modern Sardinia and it is thought if you have ancestors

stem from the region between Sardinia and the Alps, there is a chance you could

be related to Ötzi. Found in the Ötztal Alps between Italy and

Austria, he was given the nickname Ötzi and represents Europe's oldest known

natural mummy.

He is believed to have been murdered as the arrowhead in his left shoulder

was a fatal wound. He had brown eyes, O-type blood, was lactose intolerant and

probably had Lyme disease. Analysis of his colon showed Ötzi's

second-to-last meal included ibex meat, cereals and plants. His last meal

included red deer meat, grasses and cereals. He had a gap in his smile, lacked

wisdom teeth and also had a fairly rare condition where he lacked the smallest

ribs on either side.

Read more here

Thuringian Princess of Hassleben

An ancient cemetery was discovered in Hassleben Thuringia which remained

the richest ancient grave found in Germany for almost a hundred years. Not only

was the oldest written Germanic word ever discovered etched onto a comb, but

hundreds of Roman coins, ceramic fragments and Roman-style brooches were also

discovered. This is no accident as much of our knowledge regarding Thuringia and

broader Germania comes from the Roman historian Tacitus. The Elbe Germanic

tribes who moved into this region were allies of the Romans who were trading

partners, a buffer to the neighbouring Chatti - sworn enemies of Rome, as well

as specialised in metalworking of iron and precious metals.

Here you can see the richly outfitted grave of the Princess of Hassleben

which demonstrates the influential noble class who had a very close relationship

with the Romans. She was a young woman buried with a choker, golden fibulae, a

ring, a collier of roman glass beads, roman coins, pottery plates and vessels.

In her mouth was a Roman gold coin - known as Charons obol - which would provide

payment to Charon the ferryman to allow her soul to reach the world of the dead.

Next to her remains lay the skeleton of a small dog - possibly her personal pet.

Read more here

Join Our Community

Our Community blog is your hub for the latest discoveries in ancient DNA, archaeology, and lost civilizations.

Stay curious, stay connected.

Stay curious, stay connected.

Contact Us:

EMAIL

INFO@MYTRUEANCESTRY.COM

MAILING ADDRESS

MyTrueAncestry AG

Seestrasse 112

8806 Bäch

Switzerland