Compare your DNA to 168 Ancient Civilizations

FIND THE HISTORY OF YOU

So, you've got your DNA results? To discover who you really are, you need to know where you come from. We can take your DNA results one step further through the use of advanced archaeogenetics

How It Works

Uncovering your ancient ancestry is simple with our three-step process.

Take a DNA Test

Get tested with one of the major DNA testing companies (e.g. AncestryDNA, MyHeritage, FamilyTreeDNA, DanteLabs etc.).

Download Your Raw Data

Download your raw DNA data file from your testing provider's website. We support all major formats.

Upload & Explore

Upload your DNA file to our secure platform and receive your detailed ancestry analysis within minutes.

DIG DEEP

Into Your Ancient History

Your DNA, fully visualized

Explore your roots with exclusive dynamic graphs, interactive maps, and ancestral timelines designed to bring your ancient past to life.

Why Choose MyTrueAncestry

Discover what sets our ancient DNA analysis apart from traditional ancestry services.

100% Anonymous Insights

All retained data is fully anonymized, ensuring your privacy is completely protected.

Powered by Real Ancient DNA

The only service powered by real ancient DNA samples from all over the world and advanced archaeogenetics technologies.

Try For Free

Our basic analysis is 100% free for you to try with no payment method required.

BROWSE OUR DNA SPOTLIGHTS

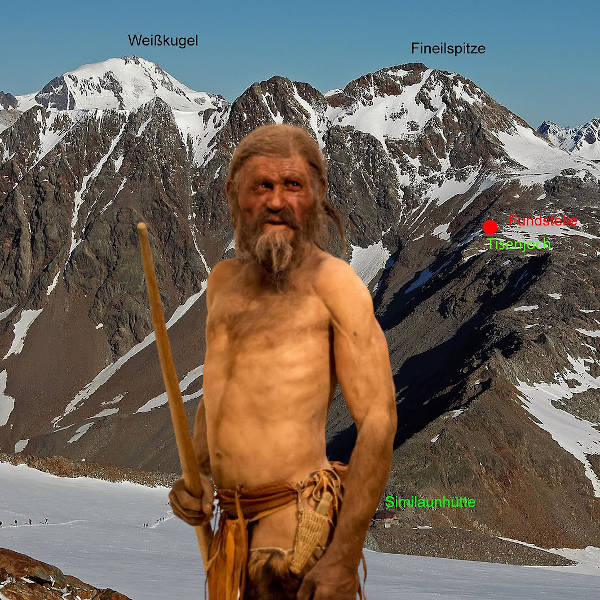

Ötzi the Iceman

In 1991, hikers discovered the mummified remains of a man who died 5300

years ago in the Alps with an arrow stuck through his shoulder. His genetics

show great affinity to modern Sardinia and it is thought if you have ancestors

stem from the region between Sardinia and the Alps, there is a chance you could

be related to Ötzi. Found in the Ötztal Alps between Italy and

Austria, he was given the nickname Ötzi and represents Europe's oldest known

natural mummy.

He is believed to have been murdered as the arrowhead in his left shoulder

was a fatal wound. He had brown eyes, O-type blood, was lactose intolerant and

probably had Lyme disease. Analysis of his colon showed Ötzi's

second-to-last meal included ibex meat, cereals and plants. His last meal

included red deer meat, grasses and cereals. He had a gap in his smile, lacked

wisdom teeth and also had a fairly rare condition where he lacked the smallest

ribs on either side.

Read more here

Dorset Viking Massacre

On Ridgeway Hill in the County of Dorset, a mass burial was found with the

remains of 54 males. These individuals had all been executed in a gruesome

manner with their decapitated heads dumped together in a large pit.

Interestingly enough all of the sharp blade wounds had been struck from the

front, meaning these individuals had faced their enemy. Radiocarbon dating

showed the bodies were from 890-1030 AD. Strontium isotopes found in the bones

show these individuals were originally from Scandinavia.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which had been written around 890 AD, provides a

year-by-year account of all the major happenings in Anlgo Saxon England.

Aethelred the Unready had been king from 978-1016 AD - it is quite possible

these bodies died during his reign. Initially the king had paid Viking raiders

off with over 10,000 pounds to stop raiding their lands. Later they began hiring

Norse mercenaries to fight off the invading Vikings - however these mercenaries

would switch sides frequently and proved too risky.

Read more here

Danish Viking Clan

Beginning in the 8th century, the Danes began a long era of well-organized

raids across the coasts and rivers of Europe. Large areas outside Scandinavia

were settled by the Danes including what became know as the Danelaw in England,

the Netherlands, northern France and Ireland. Two Viking warriors from the same

clan separated for more than 1000 years and have finally been reunited at the

Danish National Museum in Copenhagen.

Danelaw was established as an area ruled by Vikings and extended across

much of England. A group of fairly young Viking warriors was found here buried

in a mass grave near the church where they had been killed by orders from King

Aethelred II, King of the English. The warrior hilighted here was in his 20s and

died from injuries to his head. He had sustained 8 to 10 hits to the head and

several stab wounds to the spine.

Read more here

Join Our Community

Our Community blog is your hub for the latest discoveries in ancient DNA, archaeology, and lost civilizations.

Stay curious, stay connected.

Stay curious, stay connected.

Contact Us:

EMAIL

INFO@MYTRUEANCESTRY.COM

MAILING ADDRESS

MyTrueAncestry AG

Seestrasse 112

8806 Bäch

Switzerland