Compare your DNA to 168 Ancient Civilizations

FIND THE HISTORY OF YOU

So, you've got your DNA results? To discover who you really are, you need to know where you come from. We can take your DNA results one step further through the use of advanced archaeogenetics

How It Works

Uncovering your ancient ancestry is simple with our three-step process.

Take a DNA Test

Get tested with one of the major DNA testing companies (e.g. AncestryDNA, MyHeritage, FamilyTreeDNA, DanteLabs etc.).

Download Your Raw Data

Download your raw DNA data file from your testing provider's website. We support all major formats.

Upload & Explore

Upload your DNA file to our secure platform and receive your detailed ancestry analysis within minutes.

DIG DEEP

Into Your Ancient History

Your DNA, fully visualized

Explore your roots with exclusive dynamic graphs, interactive maps, and ancestral timelines designed to bring your ancient past to life.

Why Choose MyTrueAncestry

Discover what sets our ancient DNA analysis apart from traditional ancestry services.

100% Anonymous Insights

All retained data is fully anonymized, ensuring your privacy is completely protected.

Powered by Real Ancient DNA

The only service powered by real ancient DNA samples from all over the world and advanced archaeogenetics technologies.

Try For Free

Our basic analysis is 100% free for you to try with no payment method required.

BROWSE OUR DNA SPOTLIGHTS

Danish Viking Clan

Beginning in the 8th century, the Danes began a long era of well-organized

raids across the coasts and rivers of Europe. Large areas outside Scandinavia

were settled by the Danes including what became know as the Danelaw in England,

the Netherlands, northern France and Ireland. Two Viking warriors from the same

clan separated for more than 1000 years and have finally been reunited at the

Danish National Museum in Copenhagen.

Danelaw was established as an area ruled by Vikings and extended across

much of England. A group of fairly young Viking warriors was found here buried

in a mass grave near the church where they had been killed by orders from King

Aethelred II, King of the English. The warrior hilighted here was in his 20s and

died from injuries to his head. He had sustained 8 to 10 hits to the head and

several stab wounds to the spine.

Read more here

St. Brice's Day Massacre

Aethelred II, known later as the Unready, was King of the English from

978 to 1013 and again from 1014 until his death. He came to the throne at the

age of 12 after his half brother was murdered. At the start of his reign, Danish

raids on English territory began in earnest. Aethelred defended his country by a

diplomatic alliance with the duke of Normandy. The Battle of Maldon on 11.

August 991 AD involved 2,000-4,000 fighting Viking men led by Olaf Tryggvason

against the Anglo-Saxon leader Byrhtnoth who was the Ealdorman of Essex. This

ended in defeat for the Anglo-Saxons and King Aethelred was forced to pay

tribute, also known as Danegeld, to the Danish king. This payment of 10,000

Roman pounds of silver was the first example of Danegeld in England - a pattern

which would follow. The Danish army continued ravaging the English coast until a

Danegeld of 22,000 pounds of gold and silver was paid - at which point Olaf

Tryggvason promised to never return. Viking attacks only grew worse - Danish

raids would follow leading to an even larger Danegeld payment of 24,000 pounds

for peace in the Spring of 1002 AD.

The same year, Aethelred married Lady Emma, the sister of Duke Richard II

of Normandy in hopes of a stronger diplomatic alliance. On St. Brice's Day, 13.

November 1002, the confident yet paranoid King ordered the killing of all Danes

living on border towns such as Oxford. Aethelred described this massacre in his

own words: ... a decree was sent out by me with the counsel of my leading men

and magnates, to the effect that all the Danes who had sprung up in this island,

sprouting like cockle amongst the wheat, were to be destroyed by a more just

extermination, and thus this decree was to be put into effect even as far as

death, those Danes who dwelt in the afore-mentioned town, striving to escape

death, entered this sanctuary of Christ, having broken by force the doors and

bolts, and resolved to make refuge and defence for themselves therein against

the people of the town and the subrubs; but when all the people in pursuit

strove, forced by necessitym to drive them out, and could not, they set fire to

the planks and burnt, as it seems, this church with its ornaments and its

books.

Read more here

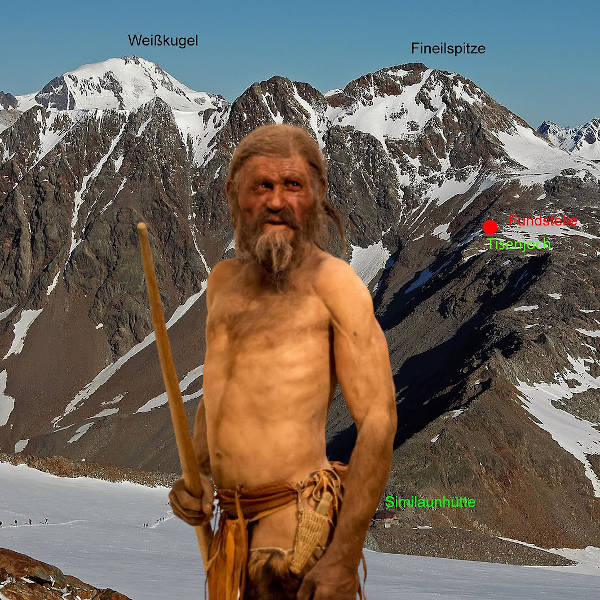

Ötzi the Iceman

In 1991, hikers discovered the mummified remains of a man who died 5300

years ago in the Alps with an arrow stuck through his shoulder. His genetics

show great affinity to modern Sardinia and it is thought if you have ancestors

stem from the region between Sardinia and the Alps, there is a chance you could

be related to Ötzi. Found in the Ötztal Alps between Italy and

Austria, he was given the nickname Ötzi and represents Europe's oldest known

natural mummy.

He is believed to have been murdered as the arrowhead in his left shoulder

was a fatal wound. He had brown eyes, O-type blood, was lactose intolerant and

probably had Lyme disease. Analysis of his colon showed Ötzi's

second-to-last meal included ibex meat, cereals and plants. His last meal

included red deer meat, grasses and cereals. He had a gap in his smile, lacked

wisdom teeth and also had a fairly rare condition where he lacked the smallest

ribs on either side.

Read more here

Join Our Community

Our Community blog is your hub for the latest discoveries in ancient DNA, archaeology, and lost civilizations.

Stay curious, stay connected.

Stay curious, stay connected.

Contact Us:

EMAIL

INFO@MYTRUEANCESTRY.COM

MAILING ADDRESS

MyTrueAncestry AG

Seestrasse 112

8806 Bäch

Switzerland